25m-high jumps become reality at Monster Jam University

Part drag car, part rally car, part low-fl ying aircraft. So we yump it

“You’re going to catch some air,” says Tristan England, driver of the JCB Digatron Monster Jam truck, the subject of this year’s Christmas road test.

This was unexpected. If you’ll excuse the behind-the-scenes indulgence, sometimes we get a brief go in a Christmas road test vehicle, sometimes an extended run, but often – if it’s, say, the Space Shuttle – no go at all.

Our first nose around the Digatron was in JCB’s test and demonstration quarry in Staffordshire, which is full of sharp immovable objects and very much ‘no go’ territory. But, suggested JCB, if you can come to the broad expanse of Monster Jam University, that can be amended.

I expected to arrive there and be given a short pootle around a yard. Instead, as I pull on fireproof race overalls, England tells me: “It’s going to be a thrill rush the whole time. Your adrenaline is going to be pumping.” Autocar is going to learn to jump a monster truck.

The JCB Digatron is one of the newest trucks running in Monster Jam, the world’s biggest monster truck series. Founded in 1992, the series easily fills huge stadiums with truck competitions that feature racing, two-wheel skills and freestyle stunt elements.

Before Monster Jam arrived, monster trucks were for the most part ordinary trucks with big lift kits and agricultural tyres, and would travel around the US putting on shows that featured, say, driving over scrap cars.

Today’s Monster Jam truck is a far more serious piece of kit, a bespoke bit of engineering, and Monster Jam itself is a vast enterprise that operates dozens of trucks across multiple events, each with tens of thousands of spectators, frequently at the same time.

It’s not unusual for there to be three, four or even five different Monster Jam events taking place at once across different stadiums, eight trucks competing at each. It’s a big business, family-friendly entertainment, and the trucks need to be extremely robust, specially engineered for reliability and durability, to perform at a level that, as England says, “can give the fans an event of a lifetime”.

It’s why one of the very newest from the box, the JCB Digatron, is a worthy subject for this year’s Christmas road test.

Design and engineering

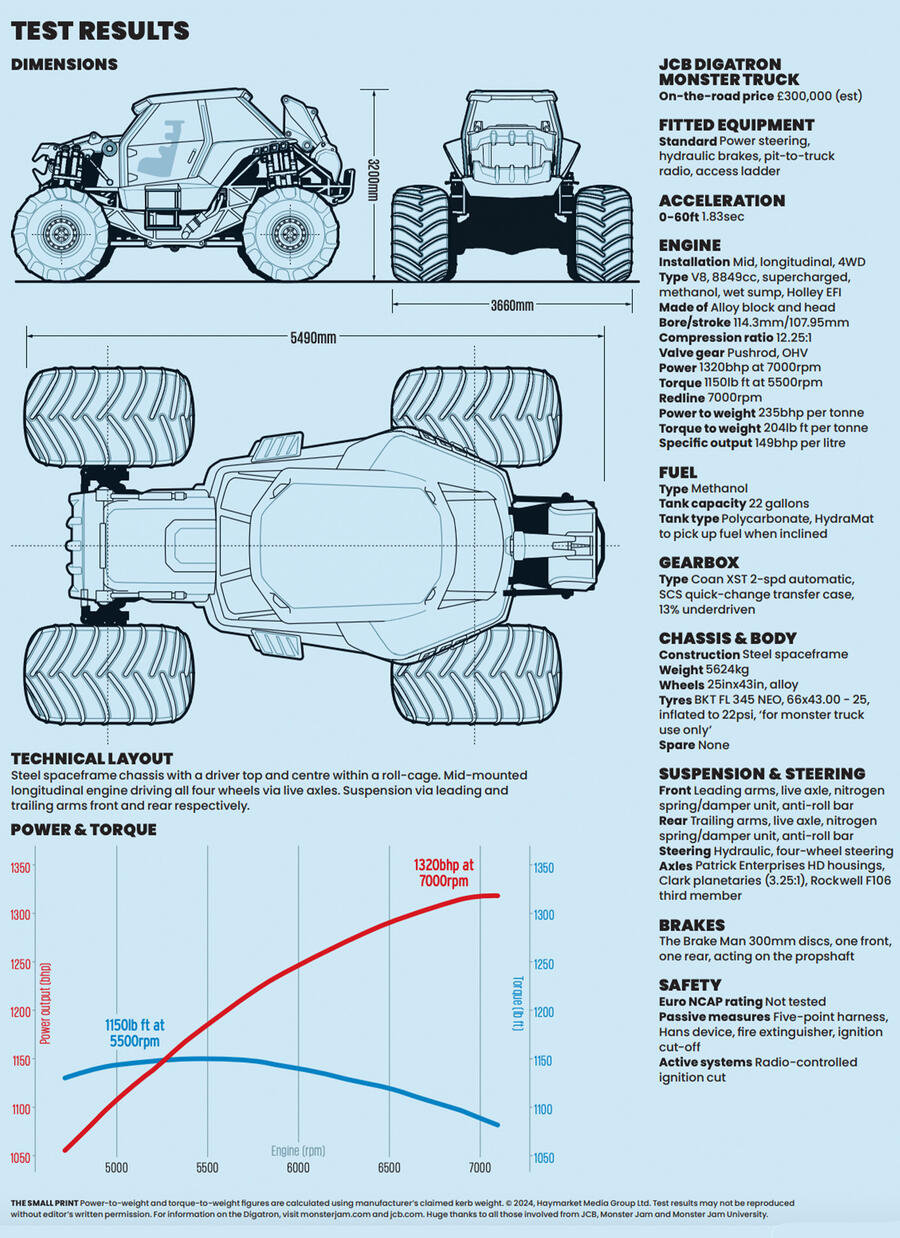

Monster Jam trucks measure 5.5m long and around 3.2m to 3.6m tall and, for the most part, the dozens that Monster Jam runs are the same as each other, save for the fact that one might look like a van and another a dog.

They all have a steel spaceframe chassis with the engine in the middle. It’s an 8.8-litre (540cu in) drag motor that burns methanol and makes in the region of 1320bhp. (US horses being the same as ours, there’s no need for a clumsy conversion.)

The motor exists to be incredibly powerful but also surprisingly durable because it must deliver oil when the truck is, say, standing on its nose for an extended period, or doing a double backflip. Essentially, it’s a modified big-block Chevy motor, wet-sumped but with various baffles and wells to keep oil flowing, and it must be very well built because they only need stripping down once every 20 hours of use.

Most mechanicals are control parts and Monster Jam looks after them, so if something blows up, whatever part is next in line is installed into that truck. The performance differences are negligible.

The engine drives through a two-speed (plus reverse) torque-converter automatic transmission, permanent four-wheel drive, to live axles that start out as military-grade but are beefed up in Monster Jam’s Florida factory, where all the trucks are made.

Braking is by discs acting on the prop shafts, one ahead of each differential. The Digatron runs mechanical limited-slip differentials front and rear: one of the few mechanical differences between trucks is that some drivers like to run a spool (locked) rear differential, but England prefers a slipper.

There are eight nitrogen-filled spring/dampers units, two on each corner, offering 76cm of travel, with leading and trailing arms locating the front and rear suspension respectively.

Steering is hydraulically actuated and incorporates a shock-bypass system so that big hits aren’t fed back to the steering wheel. This means straight ahead on the wheel is not necessarily where you left it before you turned, because the steering wheel and front wheels are linked by fluid.

There’s also active rear steer, though it doesn’t just turn the wheels the opposite way to the fronts. With the same maximum steer angle as the front wheels, they’re turned independently via a switch beneath the driver’s right thumb.

Intelligent use of rear steer not only makes a Monster Jam truck able to crab sideways or shorten its turning circle, but the good people of Monster Jam University tell me it’s also the fastest-doughnuting race car the world, and that I’ll find out later.

Wheels are 25x43in alloys with bead-locked BKT tyres, specifically designed ‘for monster truck use only’, as it says on the sidewalls, wonderfully. Monster Jam tested a few design iterations before settling on this one. They’re pumped to 22psi and their behaviour differs depending on the type of dirt.

brought into the stadium. On a fine dry dirt, they’ll wash out easily, but if it’s a little more clammy, they generate more lateral grip. Plus they last basically forever.

Monster Jam doesn’t travel with its own dirt but it has to filter what it sources locally so that spinning tyres don’t fire stones into the crowd. Similarly, unwanted flying debris is the main reason they don’t run over scrap cars any more.

Part of the spectator appeal is that, while very similar inside, Monster Jam trucks make a play of looking different on the outside. (It’s good for toy replica sales too.) So there are different roll-cage designs to accommodate.

The Digatron’s JCB-designed bodywork, reminiscent of a backhoe digger, gives it good visibility because of the amount of clear polycarbonate on it. Not that, once you’re ensconced in the cockpit, you can see a great deal.

Interior

At more than six feet off the ground, it’s quite the clamber up to the Digatron’s cabin, especially if they’ve taken off the bottom step of the aluminium ladder, making it an awkward scramble.

Your correspondent is approaching 50 and I could just get my foot onto the bottom rung of the ladder, then by gripping the top step haul myself up and through the lightweight polycarbonate-clad door and into a mostly harsh cockpit.

One only normally gets in from the left because there’s switchgear to the right, though you could climb out through the right side if you had to.

In an unusually luxurious nod, the Digatron’s aluminium seat is the only Monster Jam driver’s seat with a red leather cushion, because JCB’s diggers traditionally had them. The steering wheel is meant to mimic a JCB excavator’s too.

England and I are a similar height so I can easily reach the two pedals in front of me – a large brake and floor-hinged throttle, which has a hook over the top of it so one’s foot doesn’t slip off the pedal during manoeuvres.

There’s no need to brace oneself because the seat holds the driver so tightly. There is a five-point harness, with the cleverest way of adjusting the lap belts that I’ve yet seen: a ratchet, seemingly from a socket set, is mounted each side to click it tight, which if you’re used to hauling on a lap belt strap is a godsend.

Once I’ve tightened the shoulder straps down over a Hans device, my range of head movement is extremely limited. There are also large bolsters to the left and right of my head, essential for limiting movement when the cabin is subjected to 10g-plus impacts. One has to rely on peripheral vision for some of the switchgear.

Fortunately, it’s not like there’s a complicated touchscreen by your knees or anything, so the controls are very straightforward. England advises that I palm the steering wheel with my left hand, which steers the front wheels, while keeping my right hand on an upright metal handle, topped with a small left-right toggle switch, which turns the rears.

A finger stretch in front of that, a second toggle switch has two positions: pushed forwards, the rear wheels automatically recentre when you stop thumbing the switch; flicked backwards, the rear wheels retain whatever angle you’ve left them. It’s primarily used for doughnuts.

There is a push-to-talk radio button, a screen with rev counter and, most importantly, a temperature gauge. On a bank of switches to the right of my head, there are cut-off, ignition and starter switches, plus those for fans, fuel pump and lamps. Low to my right is the dog-legged gearlever.

It feels to me like a daunting place to sit, an unnatural environment even for somebody who drives a lot of vehicles. And that’s even before I start the engine.

Performance and handling

To start a Monster Jam truck, rotate the big red battery cut-off switch clockwise, flick on the ignition locker and push the start button. Then cower as the big-block race engine behind you vibrates your internal organs, and don’t forget to flick the supplementary switches to bring the fans and fuel pump into life.

The noise is uncomfortable. It’s quite a smooth engine but it’s loud, idling at around 2000rpm, with a quick blip of the throttle taking it to 5000rpm. But it’s a deep, stomach- and chest-troubling sound rather than an ear-splitting one.

Put your foot on the brake, haul the transmission back to first gear and, as you ease off the long-travel, steadily weighted brake pedal, the Digatron will creep forwards like a conventional automatic, on idle at a little over walking pace.

I’m doing this while England instructs me over the radio – at low revs, anyway. I won’t hear him when the taps are open. I turn the front wheels and the Digatron will respond, but it weighs 5.6 tonnes and the huge tyres are squishy, so it takes quite a lot of time for things to happen. “You have to turn early,” England has advised me already.

Rear-wheel steering makes a massive difference to responsiveness. Without it, to an extent I suppose it’s a bit like turning a trials car without using the independent rear brakes, or trying to turn a jet ski without much power on: not much happens.

With more power applied, the soft suspension and big tyres squat down, permitting weight to fall to the outside rear wheel, getting the Digatron’s power to the ground much more readily and shifting its attitude that way.

At a little over 230bhp per tonne, the power-to-weight ratio is similar to a Porsche Cayenne Turbo’s. But because the rotational masses are so much higher, it will take longer to get going and, crucially, to get stopping. I’m aware of those inertias when I’m driving it, even though I’m in a large area set aside for monster truck driver training.

I find it impossible to know exactly how fast I’m going, perhaps because the environment is so unfamiliar, because I’m so far from the ground, or because of the body movements.

If you watch Monster Jam videos, you’ll note the trucks don’t run at full throttle for very long. Even 5.6 tonnes will quickly pick up speed and run out of space in an arena. It is therefore one of the most dramatic yet also one of the slower motorsports.

A monster truck doing amazing things at 30mph looks and feels more exciting than most single-seaters going 100mph faster, which I suspect is partly the closed environment.

What I can say is that when England instructs me to “make some noise”, it gets very unsettling, very quickly, with rough terrain knocking wheels from the ground, the bumpy ride making vision blurry in an assault of vibration and noise. And all I’m doing is getting to know how it steers while doing some figure of eights around two tyres.

The only time I ever cantered on a horse I imagine it looked relatively undramatic for spectators, but from the saddle I was overwhelmed, petrified and clinging on because it felt like the least bad option.

I’m enjoying the Digatron more but finding it similarly overwhelming, with a Nascar/drag engine noise meeting a hybrid of agricultural equipment, haulage and race car engineering and huge inertia or momentum.

The combination of them all takes, one imagines, some getting used to. I’m told we should do some holeshots (standing starts) so I can feel the full acceleration.

I’m relatively familiar with these from the day job and the procedure is much the same as in a torque-converter automatic car. I put a foot on the brake pedal, gently ease the throttle down to wind some tension in the transmission, then have to put my foot harder on the brake because it just wants to drive forwards.

England pops a light from red to green at the end of a strip, I sidestep the brake and mash the throttle. He tells me that almost as soon as I’m moving, I should shift from first to second and that I’ll feel a kick in the back as I do it, which I don’t. Nor do I notice a difference in engine note. In both cases that’s because, I think, it’s too much of a rush.

Later, looking at the back of Jack Harrison’s camera, I can see the nose dip and then rise again. In the moment, there’s too much noise, blur, drama, squat and a soupçon of terror that if I don’t quite have the wheels straight, I could veer onto a nearby ramp or into a lake. And because there’s no self-centring or feel from the front wheels, I’ve only the Digatron’s general trajectory to guide me.

I try it a few times until I’m more familiar with it. My briefing notes say that next I’ll try a “1-2 shift over ramp”. When I first read that, I took it to mean I’d get a feel of what it’s like to run up and down a slope, but it transpires that means I’ll be getting air under the tyres.

Like an airport marshal, England guides me backwards to a decent starting position. There’s to be a holeshot towards a ramp and, as soon as I’m in the air, I’m told, I should lift off the throttle.

This means that the engine won’t be revving into the stratosphere. But, more importantly, the wheel and tyre combo is heavy (each weighs 300kg-plus here) and their rotational inertia can make quite a big difference to the attitude of the truck while it’s in the air.

Ideally, one would land on all four wheels at once. If I smash the throttle in mid-air, that will pitch the truck backwards; if I tap the brakes, it will pitch the truck forwards.

What I absolutely don’t want to do is land while touching the brakes because that will be “a $9000 landing” as it puts such a strain and shock through the transmission that it will break something, and it will cost £7000 to put it right.

With that warning ringing in my ears, away I go. I build up some tension in the torque converter, wait for a green light, give it death, whump into a ramp that I promise feels much bigger than it looks, and lift off when I get airborne.

On my first attempt, I think I lift before I should because the Digatron lands slightly front wheels first and it’s a little uncomfortable. I tighten my belts and am told to try again. Run two feels better.

The sort of better that I’ll still be talking about as career highlights long after I’ve retired. “You know, I once raced an Aston Martin in a 24-hour race and rode a Harley-Davidson over the Golden Gate Bridge for work,” I’ll be boring people. “And I once jumped a monster truck.”

Sure, it only went about five feet in the air but it landed so square and rolled out so smoothly that I barely felt it come down. I doubt I’ve whooped so loudly since I was a small child watching a monster truck drive over a scrap Vauxhall Nova.

I think I’ve gone miles. Of course I haven’t. The next morning England shows us just how high and far a Monster Jam truck can really go.

Buying and owning

Monster Jam runs two JCB Digatrons, one on its North American tour with Tristan England at the wheel and one that is on an international tour. That one’s in JCB’s Staffordshire visitor centre now if you’d like to see it.

At around £300,000, they’re not prohibitively expensive machines. But like buying an old fighter plane, it’s not the cost to buy that’s the difficult bit, but finding ways to use it.

Monster Jam’s organisation makes that as easy as it can. With race wheels swapped for smaller conveyancing ones, trucks drive easily into shipping containers; race trucks are accompanied by lorries with spare parts, and there are teams of mechanics, so it’s rare that a truck is rendered unable to complete an event.

Fuel consumption is lumpy at three gallons a minute, but the tyres will last as long as you need them.

Verdict

Monster trucks have come a long way since the 1970s, when they were lifted regular trucks wearing some kind of agricultural tyre. Today’s truck is a piece of precision engineering that straddles a number of forms of motorsport.

The engine is straight out of a drag car, yet has to run longer, more durably, and sometimes at 90deg to the road. And it won’t get a rebuild for 20 hours.

The chassis and suspension are as beefy as a military or agricultural vehicle’s. But the steering system attached needs to respond quickly, accurately and predictably time and again. Even if the driver has just failed to land a double backflip.

Then there’s the driving environment, which is one of the harshest in motordom. Sure, some rally cars will go faster, or deeper into dust and dirt, and they have offs too.

But they won’t have to protect their occupants from rollovers after deliberate 25m-high jumps, with six tonnes of machine pressing down on their own roofs.

A Monster Jam truck needs to have all of the durability of a piece of construction equipment, the crash-readiness and integrity of rally car, and the engine note of a drag car.

It’s a unique piece of motorsport engineering and one of the most compelling there is to see, hear and drive.

Sensational fun to watch, even more so to drive.